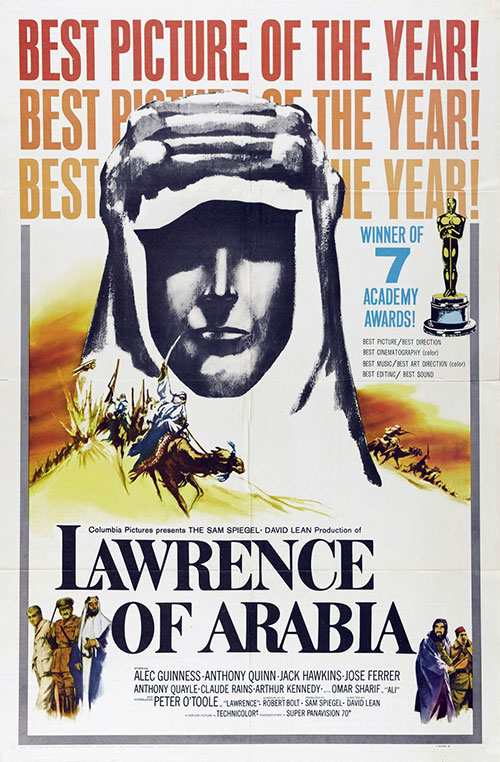

Director: David Lean

Writer: Robert Bolt, T.E Lawrence

Cast: Peter O’Toole, Alec Guiness, Anthony Quinn, Claude Rains, Omar Sharif

“T.E. Lawrence must be the strangest hero ever to stand at the center of an epic.” – Roger Ebert

“If you are the man with the money and somebody comes to you and says he wants to make a film that’s four hours long, with no stars, and no women, and no love story, and not much action either, and he wants to spend a huge amount of money to go film it in the desert–what would you say?” – Omar Sharif

Lawrence of Arabia begins with the death of T.E Lawrence.

At the end of his funeral service, a journalist approaches the mourners paying their respects and asks them for a few words about Lawrence – who he was and how he should remembered. None of the commentators could agree. Was he a hero? Some accuse him of being an egotist. Most admit that they simply didn’t know him well at all. For a man who united the tribes in the Arab Penninsula and subsequently helped the Allies drive back the Turks during World War I, he remains an enigma.

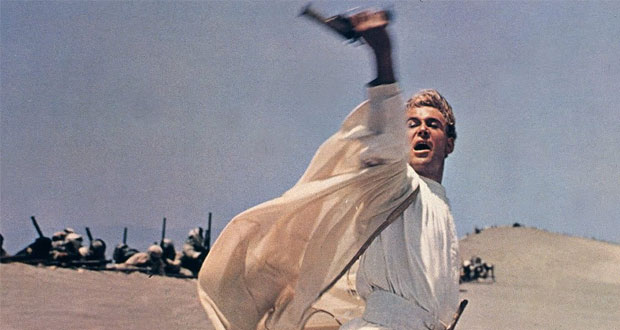

As Roger Ebert astutely observed, Lawrence of Arabia has at its centre, a most unlikely lead character for a Hollywood epic. Peter O’Toole’s portrayal of Lawrence is that of an outsider, a curious and occasionally flamboyant man who seemed indifferent to what his peers made of him. At times he seems to go out of his way to antagonize or mystify – he gives a disrespectful military salute to his superiors and he plays a masochistic game with matches – snubbing the flame with his fingers – in front of his bemused colleagues.

What’s interesting is that the O’Toole’s performance is full of these mannerisms and affectations – but the film itself doesn’t really provide any commentary on what to make of him nor does it provide much context on how Lawrence came to be the man that he is. He’s knowledgeable of the relationships between the Arab tribes, he understands the desert conditions well enough to survive them alone in extreme conditions and he is a brilliant military strategist. He is all of these things at an improbably young age and we don’t really know how or why. The real life TE Lawrence was also a homosexual and I think David Lean is to be commended for discreetly making inferences to his sexuality (as much as could be permitted in the 1960s) without any judgement. He is who he is. A man on the fringes of English society whose vision and improbable talent for diplomacy with warring Arab tribes pushes him into the lime light.

Lawrence is assigned to meet Prince Faizal, an ally of the Brits who leads an Arab revolt against the Turks. Lawrence takes on a Bedouin guide to cross the desert and meet Faisal. It is on this journey that we are treated to one of greatest entrances in cinema history. Starting as a speck on the horizon, the late great Omar Sharif marks his introduction on camel-back by shooting dead the Bedouin guide for drinking his water. We initially think his character Sherif Ali, advisor to Prince Faizal, to be a ‘cruel and barbarous’ person as Lawrence bitterly remarks. His dramatic entrance is the start of a relationship between the two men who are from different walks of life but gradually build a begrudging respect for one another.

Firstly it is Lawrence who has to win the approval of Ali. When the two men meet with Prince Faizal and a British intelligence officer, Lawrence goes against the recommendations of the British to have the Arab army retreat and he instead suggests a treacherous trek across the Nefud desert so that they can lead an assault on a Turkish garrison which is heavily armed facing seaward but is exposed on land. The journey itself is no easy feat and along the way they will need to form an alliance with the other factional and bitterly divided Arab tribes to stand a chance. Lawrence courageously offers to lead the army himself. He ingratiates himself with the Arab people with two noble acts. Firstly, he takes on two orphans – Daud and Farraj – under his care. Secondly, when one of the men named Ghasim slips off his horse unnoticed at nightfall, the other men give him up for dead. Lawrence travels back and rescues him, an act that finally wins him over with Sherif Ali.

In war, the first casualty is innocence and for every good deed that the wide eyed Lawrence performs, he is ‘rewarded’ with persecution, betrayal and death. On the eve of the invasion of the Turkish garrison, the fragile alliance between the Arab tribes threatens to blow apart when a man from one tribes murders a man from another. To prevent the cycle of vengeance that would shatter the alliance, Lawrence offers to execute the killer personally so that both tribes can remain united. He is crushed to discover the identity of the killer is none other than Ghasim.

Lawrence successfully leads the assault on the Turkish garrison, the first of many successful military campaigns. This ends Part One of the film.

Part Two of Lawrence of Arabia focuses on Lawrence’s ongoing raids against key Turkish outposts and how the relentless setbacks he faces – being ostracised by British troops, the confronting deaths of his orphaned companions and torture at the hands of Turks threatens to break his spirit.

What started as a campaign for a united Arabic alliance quickly derails into war mongering for reasons entirely different. Lawrence’s army expands but gradually becomes diluted with military guns for hire, bounty hunters attracted by money rather than the cause. It becomes Sherif Ali’s turn to act as a moral compass for Lawrence, as Ali becomes horrified by the vulgar behavior of the men he serves with. At Lawrence’s lowest ebb, his army conquers the city of Tafas. Seeing a few stranglers running in retreat, he echoes the rallying cry “No prisoners!” and slaughters the surrendering survivors. Afterwards he is overcome with remorse and left a broken man. Having outlasted his usefulness to both the Brits and the Arabs, he is promoted to Colonel and sent home.

Lawrence of Arabia is a film that is a regular fixture of Greatest Movie lists and deservedly so. The film is an expansive and remarkable cinematic production whose scope and quality is matched by precious few contemporaries. Lets face it, with the advent of modern cinema’s reliance on special effects, we will likely never again see footage on the scale of the battles we see in Lawrence of Arabia with hundreds of horseback soldiers conquering cities and engaging in combat. Shot in Jordan and Morocco, the film has a real sense of place. The cinematography by F.A Young vividly captures the unforgiving heat of the desert sun, the shimmering horizons on the sand dunes that promise a thirst quenching oasis and the stinging brutality of being caught in the eye of a sandstorm. Every square inch of the frame is utilized and some of the lasting images I have of the film are of Lawrence and Ali, walking across the desert, practically two dots on the screen, navigating a seemingly endless terrain. All this is complimented by a sweeping orchestral score from Maurice Jarre which has been imitated by virtually every film soundtrack set in the desert ever since.

Director David Lean was a master of his craft and arguably no other film creator has made three finer films in succession that Lean’s run that started in the late Fifties when he made The Bridge On The River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago back to back to back. As I mentioned earlier, the paradox of Lawrence of Arabia is that it is an intensely intimate and personal film about a man that we never fully understand. What other four hour war epic is fixated so singularly on one individual? And yet Lean doesn’t claim to have the answers when it comes to understanding what made Lawrence tick. As an audience we are left to interpret how his experiences before and during the war shaped the man that he became.

Lean never gives in to glamorizing the theatre of war and he casts an even handed level of cynicism across all its participants – from the journalist who is sent over with the explicit purpose of writing an article to whet the American appetite for war to the behaviour of both the British and Arab soldiers who are typically indifferent to the officially stated reasons for war and are more interested in self preservation or profit. Lean is able to bring this vision to life with the aid of a formidable cast of actors. It goes without saying that Peter O’Toole cemented his legacy with his nuanced and complex performance in this film but he is also in the company of some extraordinary talents – Raines, McGuiness, Sharif – each man making an important contribution to the overall quality of the production.

Lawrence of Arabia is bold and ambitious film making. It has a timeless quality about it, maintaining the capacity to awe and inspire to this very day and is best enjoyed on the biggest, widest screen you can possibly arrange. The Gold Standard in cinematic epics.

Review Overview

RATING

CLASSIC

Summary : A sprawling epic that hasn't aged a day. With a cast of thousands, a talented cast of screen legends and a four hour running time, Lawrence of Arabia sets the bar for film making on a grand scale.

The FAT Website est. 1999

The FAT Website est. 1999