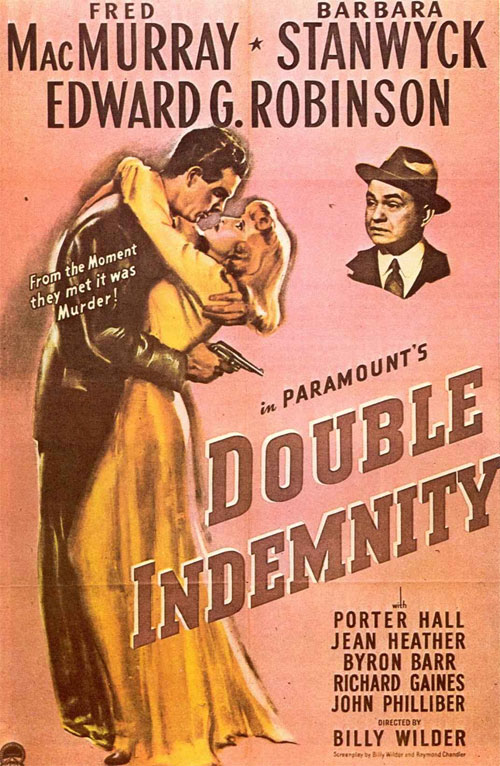

Director: Billy Wilder

Writer: Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler

Cast: Fred MacMurray, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward G. Robinson

As screen writing credits go, you don’t get much bigger names in the Forties than the pairing of Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler. Wilder is a Hollywood legend with an output of films that were of an improbably high standard across a number of different genres. Then you have Raymond Chandler, a literary giant who only produced eight books in his lifetime but his hard boiled crime detective characters and stylistic prose basically set the foundations for an entire genre. Their collaborative efforts on Double Indemnity do not disappoint. This is a true film noir classic.

The film begins with the longest and most protracted death scene in cinematic history. It’s an unwritten rule of film noir that you have a narrator and in this instance that person is insurance salesman Walter Neff, played by Fred MacMurray. Neff gets mortally wounded by a gunshot and then he walks outside, has a conversation with a young man, drives to work in his car, walks into his office, dictates a murder confession that takes ninety minutes to explain and then he keels over dead.

Neff is an ordinary jobsworth who has worked in insurance sales all his life. He has the admiration and trust of his boss Barton Keyes who wants to lure him into a desk job sniffing out insurance fraud but Neff’s passion is for being on the road and selling.

His life takes a twist when he visits the home of oil baron Mr Dietrichson with the intention of renewing his auto insurance. Dietrichson is away but his bored, lonely housewife Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck) sure isn’t. She makes a memorable first appearance at the top of the stairwell wearing nothing but a towel. Neff’s eyes light up and even though its 1944 and the Code placed pretty tight guidelines around what actors could say onscreen, Wilder and Chandler’s innuendo laden dialogue shines through. “I’d hate to see you get a smashed fender when you’re not fully covered” remarks Neff.

I don’t believe Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck were ever a real life item but their chemistry onscreen is fantastic. Neff’s body language and twinkling gaze signal his intentions for all to see and Stanwyck, for her part, hits just the right notes as the coy femme fatale who draws Neff into her web. They talk in doublespeak, saying one thing, inferring another. I’ve never heard a sexier conversation about insurance paperwork and contract renewal in my life.

I love this exchange in particular:

Phyllis: There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff. Forty-five miles an hour.

Walter Neff: How fast was I going, officer?

Phyllis: I’d say around ninety.

Walter Neff: Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket.

Phyllis: Suppose I let you off with a warning this time.

Walter Neff: Suppose it doesn’t take.

Phyllis: Suppose I have to whack you over the knuckles.

Walter Neff: Suppose I bust out crying and put my head on your shoulder.

Phyllis: Suppose you try putting it on my husband’s shoulder.

Walter Neff: That tears it.

Naturally the two get together but that is only the beginning. Neff lusts after Phyllis but she is ultimately unattainable with her husband in the picture. Phyllis gladly spoon feeds him an idea to change all that. She makes herself out to be a lonely and miserable house wife, trapped with no where to go and no money of her own. She suggests a life insurance policy be taken out on her husband against his knowledge. Neff concocts a policy with a clause that pays double in the event of an accident. Together they hatch a plan. But not before Neff relieves some stress by going to a drive-thru pub where you can chill in your car and drink beer (!).

Neff and Phyllis succeed in staging Mr Dietrichson’s death but there’s two things they don’t count on. First, there’s a witness on a train that asks too many questions and threatens to spoil their elaborately constructed suicide. Second, Neff’s boss Barton Keyes smells a rat. Keyes is played by Edward G Robinson who plays the part with relish. Keyes is a proud of his intuition when assessing insurance claims and he proudly defers to the innate sense of ‘the little man’ inside him who knows when something isn’t right. The second half of the film is wrought with tension as the net closes in on Neff and Phyllis and they begin to panic and turn on one another.

Double Indemnity is a much loved classic of American cinema and with good reason. The film is hugely influential in establishing the visual language, the personalities and the soul of noir cinema. Neff and Phyllis are captivating leads who wear a vulnerability on their sleeve when they pine for one another but are quick to turn ruthless and cold blooded when their plans fall away and their personal liberty becomes compromised. Keyes is admirably single minded in tracking down the truth to Mr Dietrichson’s death, seemingly unaware that the culprit is the very man he bounces ideas off of to try and solve the case. Even though Neff, Phyllis and Keyes are all pitted against one another at various stages, I found myself willing on all three.

Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won zero. Perhaps its dark and nihilistic soul was too much for an Academy who just two years prior showered recognition on Casablanca, an equally wonderful film but one that is infinitely more optimistic and wide eyed. Double Indemmnity is a nasty film about selfish people doing unspeakable things to get what they desire. It’s the essence of film noir.

Review Overview

Summary : A cornerstone of the film noir genre that features three great performances from Stanwyck, Robinson and MacMurray. Double Indemnity is nihilistic film making at its finest.

The FAT Website est. 1999

The FAT Website est. 1999